calms an anxious mind without pharmaceutical medications

To add milestones and tasks to your plan, please send them via e-mail to info@karolinafund.com. Tell us which tasks you have already finished (checked) and which ones are left.

Showing what the plan is for your project helps build trust with potential backers.

Financial insecurity can cause frustration and worries which affects the nerve system. The Solar Plexus is a dense cluster of nerve cells and supporting tissue, located behind the stomach in the region of the celiac artery just below the diaphragm. It is also known as the celiac plexus and is a crucial connection to the brain. The Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ is a Deep Touch Pressure (DTP) technology that stimulates the Solar Plexus and calms an anxious mind - A medicine-free treatment.

Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ was inspired by Helgason’s own experiences as a creative practitioner suffering from anxiety and panic attacks in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. A decade later the mode of economic ‘crisis’ has become normalised. Temporary, insecure forms of employment that were once marginal, are now integral to the function of the economy, and part of its inherent logic (Berardi, 2005b). These structural changes are directly impacting the laborer’s body and neural system. The design of the belt simulates a finger pressing into the solar plexus area, a motion and coping mechanism Helgason discovered would reduce feelings of stress and anxiety, leading him to further investigate the underlying neurological processes. Acknowledging his own entanglement within late capitalism, Helgason proposes a new product, the Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™, designed to temporarily reduce discomfort until an economic system is found that provides financial security to all inhabitants.

With the help of Karolina Fund we would like to finance the production of the BETA edition of the Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ for testing and feedback purposes.

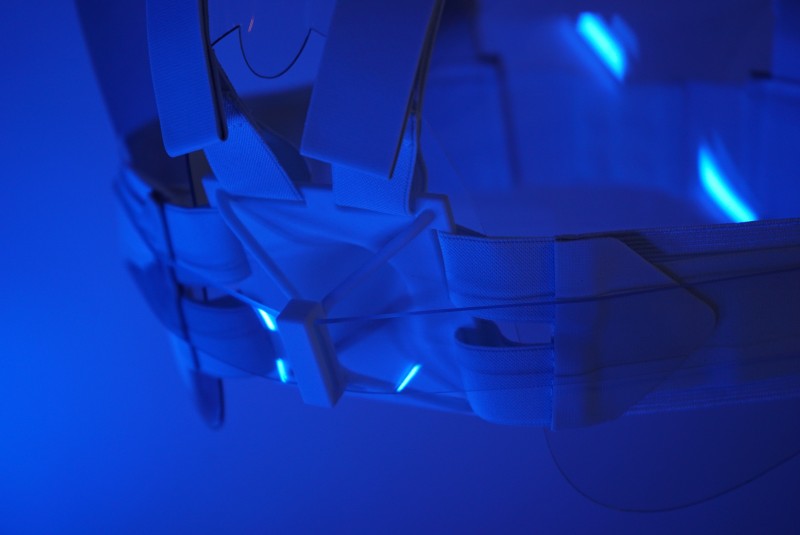

Those who support the project of €250 or more will receive a limited BETA edition of the belt together with a transparent plexiglass torso. When not worn, it serves as a artwork in a limited edition of 50 (signed and numbered).

This project is produced by Fellowship of Citizens, an interest group founded in october 2017 with the aim of lobbying for basic income. By supporting this project, you also contribute to their good work.

A shift into late-capitalism from 1945 onwards has entailed economic restructuring on a global scale, with industrialised countries reorienting towards a service economy, with an increasing significance in the information and communications sectors. As part of this cognitive-cultural capitalism (after Hardt and Negri, 2000), and the emergence or growth of the hi-tech, media and cultural industries, there has been a change towards a new kind of contemporary labour and ‘productivity’. Cognitive labour instrumentalises intellect, creativity and affect in an ‘attention economy’, relying on processes ‘occurring in the factory of the brain’ (Neidich, 2014) to generate profit. However, combined with neoliberal deregulation and precarious employment, this has produced the precarious cognitive labourer or ‘cognitariat’ (after Berardi, 2005). This is often referred to as ‘immaterial labour’, as there are fewer ties to a physical product ora geographically-specific workplace, but this doesn’t mean that there aren’t material impacts or social differentiations. For example, different forms of labour are attributed with binary-gendered associations, with affective labour being perceived as ‘feminised’ (Federici, 2006), and the expanding information, software and hi-tech industries being perceived as more ‘masculine’ realms. ’Semiocapitalism’ (Baudrillard, 1976) is a crisis of ‘overproduction’ or saturation of cultural symbols and their subsequent devaluation or destabilisation. There is both an acceleration of activity, but with a loss or exhaustion of meaning, which leads to a ‘psychology of the disinvestment of desire and the triumph of drive’ (Lash, 2014). Impacts or symptoms of the changing socio-material environments of late-capitalism include an increase in mental health issues, such as anxiety and panic disorders, ADHD, depression and sleep disorders. These are concurrent with new technologies, digital social networks, and ‘the production of psychic stimulation…that create a sort of continuous excitation, a permanent electrocution, which leads the individual mind as well as the collective mind to a state of collapse’ (Berardi, 2009). These issues, often seen as ‘pathological’ manifestations, may be a completely proportionate response to the changing structural conditions. As well as the geographical dispersal of the workforce, a neoliberal ideology that favours state spending cuts and increasing privatisation and outsourcing, has led to a systematic undermining of labour rights, where most workers are in increasingly insecure or ‘flexible’ employment. There is a simultaneous requirement of ‘professionalisation’, but one that prioritises adaptability rather than specific material skills or knowledge, with a pervasive acceptance of temporary, precarious working conditions as the new norm. In a ’24/7’ culture the employee is expected to be constantly ‘available’ to work (even when not ‘at work’), where the basic diurnal rhythms of the human body are disrupted. This disjuncture invokes anxiety and hyper-vigilance as physiological responses, symptomatic of wider structural conditions of ’24/7’ culture as ‘a state of emergency… (that) become(s) domesticated into a permanent condition’ (Crary, 2014). Penzin (2014) states that the essential feature of contemporary capitalism is its ‘uninterrupted..continuity’, where time is both commoditised, but also rendered meaningless or increasingly amorphous: ’a time without time, extracted from any material or identifiable demarcations, a time without sequence, orrecurrence’ (Crary, 2014). Sleep deprivation has physiological effects that lead to anxiety and exhaustion. However, through the eyes of capital, sleep is in itself presented as somehow pathological or obstructive to productivity; or, alternatively, it is instrumentalised in attempts to either reduce the number of hours of sleep or ‘maximise’ sleep quality for increased worker ‘productivity’. After the 2008 global financial crash, the mode of economic ‘crisis’ has become normalised. Temporary, insecure forms of employment that were once marginal, are now integral to the function of the economy, and part of its inherent logic (Berardi, 2005b), with a return to feudal mechanisms of rent and debt (Neidich, 2014). Economic insecurity produces astate of anxiety and competition, and as work-life boundaries are increasingly blurred, this hyper-vigilance is no longer specific to the workplace but all-pervasive. Even outside of ‘work’, individuals have internalised the attitude of the workplace to self monitor their ‘productivity’ and ‘output’. Despite increasing abstraction and‘dematerialisation’ (or changing material conditions), these behaviours impacts the body and there are real, material impacts on the brain and nervous system.

Understandings and perceptions of ‘mental health’ or ‘wellness’ vary globally, nationally, culturally and ideologically, as do their treatments. There are different constructions of psychiatric conditions, from biomedical, individual and familial models, to acknowledging wider sociopolitical contexts. In high-income countries mental health treatment is individualised rather than looking at extended family, peer and community support networks as tends be the case in lowerincome countries (Thornicraft, 2015), and treatment is outsourced to professionals providing therapy and medication. In certain geographical locations with industrialised or industrialising economies, there has been an increase in specific mental health conditions; Anxiety disorders are increasingly common in the U.S, effecting 18.1% of population (1), and a 42% increase in ADHD diagnoses in the US in past 8 years (APA 2018, CDC 2018). 6.6 percent of the Japanese population have depression and mood disorders (JCPTD, 2018), however, with a different demographic distribution than Western societies, where depression is prevalent in both youth groups and the elderly. Despite a common perception in Western culture that anxiety and panic disorders are related only to lifestyle changes and consumerism, WHO reports depression and anxiety disorders as the leading cause of disability globally, and while specific rates vary in frequency and type by demographic, the majority of people in developing countries remain untreated (WHO, 2018). China and India, which are experiencing rapid industrialisation and social change, disproportionately bear the burden of mental health disorders globally (GBD, 2013). There has been an overall global increase in reported mental health issues, perhaps in part due to increased research, funding and education, but also with changing material conditions where contemporary globalisation and its economic restructuring has led to increased precarity for all (except the 1% elite). The most marginalised, precarious workers are impacted, including agrarian workers, where suicide rates among rural indian farmers increased from 1990s onwards, impacted by the pressures of debt and increasing environmental problems with climate change. With this continuing, unsustainable form of industrialisation and the rapid socioeconomic change it brings, the rates of mental disorders are projected to increase, and their treatment will vary according to state infrastructures available and sociocultural contexts including stigmas or taboos of addressing and dealing with mental health. A response to this has been the use of medication, where in the US population "long-term antidepressant use” is common (NCHS, 2018); though this may be indicative of the problem, it is also shows a tendency to over-prescribe that is tied to the profit based pharmaceutical industry, rather than to address structural causes like inequality and precarity. Achieving an optimum level or combination of medication is mostly trial and error, and has only proved to be effective if combined with other forms of therapy in a holistic approach. However, with neoliberalism, and decreased funding of state healthcare in ‘welfare state’ countries, it has increasingly become the responsibility of individuals to take on the burden of care. Capitalising on the gaps in healthcare services with long waiting lists or insurance costs, products or services are sold to help them cope with wider structural changes; however, this assumes that they have a disposable income to buy them. Additionally, many ‘alternative’ practices of achieving emotional or spiritual fullness and wellbeing have also been co-opted in the burgeoning self-help and wellness industries.

(1) Including Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) Panic Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder SAD and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

When under perceived ‘threat’ the fight-or-flight mechanism in the sympathetic nervous system is temporarily provoked, until the ‘threat’ subsides. However when this threat is constant, the brain’s neural pathways and biomolecular structure change, where certain pathways become sedimented and perpetuate hyper-vigilant responses. Yet these neural pathways are malleable and changeable, and can be re-shaped. People have adopted many methods to reduce distressing physiological responses, such as Deep Pressure Therapy. Different techniques include deep massage and deep vibration, which can be partly imitated by a ‘hug machine’ or ‘squeeze machine’, or more portable technologies like weighted blankets, lap pads and vests, compression garments, and now the Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™. Deep Pressure Therapy works by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system, which regulates involuntary mechanisms like heart rate and blood pressure, to slow down the fight-or-flight response in the body, relaxing the muscles,improving circulation and producing endorphins. The Solar Plexus is located on a person’s torso, below the sternum and line with the stomach; it is the point at which the body’s sympathetic nerves intersect, and are radially connected to the major organs in the abdomen. Upon pressing into the Solar Plexus, many people have found that it helps stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, and reduces feelings of anxiety and distress. The Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ draws on these experiences, and was designed to allow people to self-administer Deep Pressure Therapy. This can be a feasible alternative for distress-reduction, especially for people who do not want to experience the potentially disruptive side-effects of prescribed pharmaceutical medications. As well as relaxing the physiological responses of the individual, The Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ also contributes in some way towards structural change, through the Fellowship of Citizens campaign for a solution to financial insecurity through Basic Income. The Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ offers an affordable, sustainable method for individuals to cope with the instability and stresses of their socio-material environment, but can only be truly effective if used in combination with collective action to instigate longer-term structural changes.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (APA) Online: https://www.psychiatry.org/. Accessed: October, 2018

Baudrillard, Jean (1976) Symbolic Exchange and Death (Theory, Culture & Society) Sage Publications.

Berardi, Franco (2005) What does Cognitariat Mean? Work, Desire and Depression. https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/article/view/3656.

Berardi, Franco (2005)b Info-Labour and Precarisation. Translated by Erik Empson Online: http://eipcp.net/transversal/0704/bifo/en, April 2005.

Berardi, Franco (2009) Precarious Rhapsody: Semiocapitalism and the pathologies ofthe post-alpha generation http://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/PrecariousRhapsodyWeb.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), US Department of Health, Online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/timeline.html Accessed: 2018.

Crary, Jonathan (2014) 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. Verso: London.

Federici, Silvia (2006) “Precarious labor: A feminist viewpoint” lecture (2006), reproduced in “Precarious Labor and Reproductive Work” on https://caringlabor.wordpress.com July 29, 2010. Accessed: October, 2018.

Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study (2013) WHO and World Bank. Online: http://www.healthdata.org/ Accessed: 2018.

Hardt, M. and Negri, A. (2000) Empire, Harvard University Press.

Japan Committee for Prevention and Treatment of Depression (JCPTD) (2018) Online: https://www.jcptd.jp/ Accessed: 2018

Lash, Scott (2014) The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism, Conference at Goldsmiths University, London (May 2014).

National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2018). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/index.htm Accessed: 2018.

Neidich, Warren (2014). The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism, Conference at Goldsmiths University, London (May 2014).

Penzin, Alexei (2014) The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism, Conference at Goldsmiths University, London (May 2014).

Thornicraft, Graham (2015) Discussion with the author at the Centre for Global Mental Health at King’s College London (April, 2015).

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2018) Online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders. Accessed: October, 2018.

Karolina Fund ehf © 2025 | Kt: 460712-1570 | VAT: 111464 | Bjargargata 1, 102 Reykjavík, Iceland